Central Park North’s allure has yet to approach that of other stretches edging the world’s greatest urban park—which in many ways stupifies when you consider that the views are just as good, if not better than those from any other city vantage. Developers have long ignored the area, deeming it too far-flung to draw in monied buyers.

The neighborhood’s rep, however, is beginning to shift, particularly as Central Park South becomes overpopulated with skinny, soulless glass towers, and the commercial hazards of the Upper West Side creep further and further northward. Central Park North by comparison handily presents itself as a more agreeable, vibrant, and human-scale alternative.

One of the newest luxury developments to sprout on the upper edges of the park is 145 Central Park North (145 CPN). The 13-story residential edifice finished construction this month and is the work of NYC architecture firm GLUCK+.

GLUCK+ designed 145 CPN to be in context with the park and its surrounding neighborhood with the building’s aesthetic harkening to the historic fabric; its modern inclinations are exhibited only subtly in eye-level details and more boldly above street-level sightlines where you will see the building’s top floors wrapped in an all-glass skin.

Ahead, GLUCK+’s principal, Thomas Gluck, talks to Urbanize NYC about the design of 145 CPN, what the building means for Harlem, and what the city needs to do to foster more affordable housing. Gluck is a longtime resident of over 25 years and his studio is also firmly established on West 127th Street.

Urbanize NYC: How did GLUCK+ become involved with the design of 145 Central Park?

Thomas Gluck: This project is a joint partnership between Manhattan-based developer GRID, and a Belgian real estate company. They acquired the property when it was just a vacant building.

GRID came to us because they are very hands-on developers who are also builders. They were looking to foster a relationship with a similarly minded high-design architect who could bring significant architectural value to the project given the importance of the location on Central Park. Because of their background, they loved the fact that we’re also contractors. Unlike almost every design firm in the country, we build a lot of our own buildings, and on this project we are both the architect and the contractor.

Beyond that, I think because our studio is in Harlem, and a lot of our employees live around here, they appreciated the fact that we have both knowledge and an avid interest in the neighborhood.

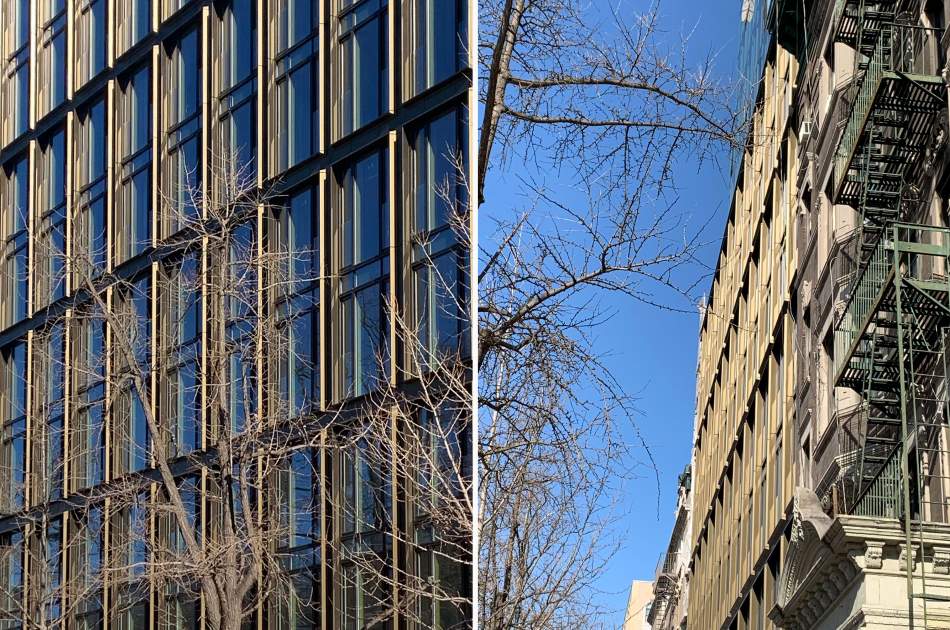

Central Park street wall | GLUCK+

Central Park street wall | GLUCK+

Urbanize NYC: Can you speak a bit about the design of 145 Central Park North and the inspiration, particularly as it relates to the materiality? There is clearly a unique dialogue happening between the bronze, the glass, the street, and the park.

Thomas: The most important piece of this building is that it is part of the street wall of Central Park, one of the most iconic urban spaces in the world. Along this historic urban space there are a number of really important and expressive buildings, like the El Dorado, the San Remo, and the Guggenheim Museum. In this context, the question for us was “What do we do here?” because whatever we do really matters.

Our design had to be two things: 1. an iconic building that would be attractive to potential buyers and worthy of its privileged location on Central Park; and 2. a building respectful of its context. We wanted it to be a good neighbor and enhance the street-level experience as well.

Entry to 145 Central Park North | GLUCK+

Entry to 145 Central Park North | GLUCK+

We pulled cues from the neighborhood context by using a traditional tripartite scheme but modernized it in a way that reflects the conditions of our time. At street level, in place of a rusticated base, there is a staccato rhythm of stone and glass panels; in the middle, a deeply textured curtainwall highlighted by bronze-like extruded metal frames terminates in a false cornice; and above, a quiet reflective volume of four-way structural glass that minimizes the height above the neighboring midrise buildings. The glass absorbs and reflects what’s around it—the city, sky, and the different weather conditions. As a result, you perceive a building that is much lower than it actually is.

Another tool we implemented to minimize the perceived scale was to aggregate two floors within the articulated frame. By doing this, it appears the middle section is only four-stories tall when in actuality it is eight.

A lot of modern buildings are also very flat, so to make this building feel rich, more contextual, and weighty, we applied deep profiles that create a façade that changes with the light as you walk down the block. From a distance the façade closes upon itself, appearing as part of the texture of the city but as you approach it, the large expanses of glass are revealed becoming an identifiable building in its own right.

Street view of 145 Central Park North, January 2020 | GLUCK+

Street view of 145 Central Park North, January 2020 | GLUCK+

A close-up look at the facade | GLUCK+

A close-up look at the facade | GLUCK+

Urbanize NYC: And all the units have views of the park?

Thomas: The conceptual driver of the whole project is really the park. It's very much focused on its immediate context and its relation to the park.

The site is shallow at only 70 feet deep. This provided an incredible opportunity where we could keep corridors to a minimum in the center allowing the majority of apartments to have views both to the park but also north to the rest of Harlem. Harlem is primarily in a R7-2 zoning district, which means the buildings are relatively low, so you have great views looking both north and south. The shallow site also enabled us to plan the building such that every single apartment has frontage on the park; we have 37 units with 37 views of Central Park. We wanted to make the experience of the park central, so the kitchen and living and dining rooms are stretched out wide across a large expanse of glass with multiple operable windows.

Views from a model unit onto Central Park | Evan Joseph

Views from a model unit onto Central Park | Evan Joseph

The glass system is an aluminum curtain wall—it’s kind of the standard in the industry—but in order to have the interior experience be more intimate and connected to the park we wrapped it in the same white oak that we have on the floor. So what we’re doing is framing the views of the park with a softer, warmer, more natural material than you’d have with exposed aluminum. This treatment really transforms your relationship to Central Park and the experience of the interiors. You really feel like your porch is the park.

Urbanize NYC: You're a longtime resident of Harlem, what responsibility did you feel towards the neighborhood and community with this design? Especially as the units are out of the market range of most local residents.

Thomas: I grew up in Morningside Heights and moved to Harlem 15 years ago when I returned to New York. Since then, south Harlem has gotten really quite fancy; it's really an extension of the Upper West Side now, which, of course, is what generates projects like this.

But this is a topic we've actually talked a lot about internally because we do a lot of projects in Harlem and upper Manhattan. We feel good about our practice because we take on a wide range of work and that includes market-rate multifamily buildings like 145 Central Park North but also a large number of not-for-profits, public charter schools, and 100 percent affordable housing projects. We recently completed a tennis center in Crotona Park in the Bronx that houses an afterschool tennis and education program that serves upwards of 85,000 New York City kids every year.

We believe in Harlem. Our office is on 127th Street and we’ve been here in Harlem for nearly 20 years. We don't have Midtown offices and then swoop into the neighborhood. We live and work here.

But if someone comes in and asks us to design and build a building like the one we’re discussing, we’re going to say yes and we're going to try to make it a responsible building. With 145 Central Park North we made a huge effort to think about what it’s like to be on the street, what it’s like from the park, what it’s like as an urban occupant, and even how the building itself is a citizen of the city.

The displacement issue is a real one, but there are a lot of people we've gotten to know on this project and in neighboring buildings who are longtime Harlem residents and who recognize this building is good because everyone wants to live in a healthy active neighborhood.

But of course, there’s a tipping point: Are all these new buildings going to end up increasing value to the point where no one can afford them anymore? We sure hope not, but that certainly is a real fear.

Urbanize NYC: And to be fair, it’s also a city policy issue.

Thomas: Exactly. For instance, when my family moved into our apartment on 119th Street Frederick Douglass Boulevard 15 years ago, it was middle-income, subsidized housing. The neighborhood was still dominated by empty lots and abandoned buildings, and the city was subsidizing housing trying to build stability and get people into the area.

Within five or six years, the city exclusively stopped all the middle-income subsidies and switched to low-income subsidies for the rest of the properties under their jurisdiction. So essentially what they did was first stabilize the neighborhood, then preserve the demographic.

And this is why I love the neighborhood: It feels like New York City. Harlem is quintessential New York. It's diverse, there’s mixing, and it’s not homogenous. It doesn't feel like the Upper West Side, which has become a big mall.

Urbanize NYC: So, what type of development and investment would you like to see more of in Harlem? What do you think needs to happen to ensure it remains equitable?

The preservation of mixed-income housing. Whether that's mixed-income within a multi-family building or row house; it should provide both rental units and homeownership. We need more opportunities to maintain a high level of affordable housing so that things don't become so economically homogeneous, which is of course the driver for racial homogeneity.

I sincerely believe that this will never be a city of entirely rich people because that is not what a living city is.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.